BBC News Funding Calculator

The BBC UK News is funded by the TV license fee (£159/year), while the international version uses ads and may soon have a paywall. This calculator shows how funding differences affect your experience.

UK Funding Model

You pay through your TV license fee

What you get:

Funded by UK households through TV license fee. No ads, no data selling.

International Funding Model

You pay through ads or future paywall

What you get:

Funded by ads and partnerships. US paywall expected to launch June 2025.

The BBC UK News website isn’t just another news site. It’s the most visited news platform in the UK, used by 62% of all internet users in the country. But if you’ve ever compared it to the international version, you’ve probably noticed something odd: the same stories look different, behave differently, and even feel different. Why? Because they’re not the same site. They’re two separate platforms running on the same brand, built for two completely different worlds.

How BBC UK News Is Funded - And Why That Changes Everything

The BBC UK News site doesn’t run ads. It doesn’t sell your data. It doesn’t need you to click on sponsored links. That’s because it’s funded by the TV license fee - £159 per household every year. That’s not a subscription you sign up for. It’s a legal requirement if you watch live TV in the UK. In return, the BBC is legally bound to serve the public, not profits. This is why the UK version feels calm, clutter-free, and focused on facts, not clicks. The international version? Totally different. It’s run by BBC Global News Ltd., a commercial arm of the BBC. It makes money from ads and partnerships. That’s why it has social sharing buttons, article-saving tools, and a design built to keep you scrolling. The UK version doesn’t have those. Not because they’re lazy, but because they’re not allowed to chase engagement. Their job is to inform, not to hook you. This split isn’t an accident. It’s by design. The UK edition answers to Ofcom, which demands impartiality and public value. The international edition answers to shareholders and ad buyers. One is a public service. The other is a business.Design Differences You Can Actually See

Open the BBC UK News site on your phone or laptop. Look at the background. It’s off-white - #F8F8F8. Now open the international version. It’s pure white - #FFFFFF. That’s not a typo. It’s a deliberate choice. The UK site uses a two-column layout. Headlines sit on the left, images on the right. The international version uses one column, stacking everything vertically. Why? Because the international team wants you to scroll. The UK team wants you to scan. Bylines? On the UK site, they appear under the headline image. On the international site, they sit between the title and the image. Dates? The UK version shows the original publish time. The international version shows when it was last updated - because news changes fast abroad, and readers expect freshness. Here’s the weirdest part: UK users are forced to register to read articles. But they can’t save them. Meanwhile, international users can save articles to read later - and 37% of them do. The UK version doesn’t offer that feature. Why? Because there’s no commercial reason to. If you’re not trying to get users to come back, why build a save function? It’s not a mistake. It’s a philosophy.

BBC Verify: The Fact-Checking Team No One Talks About

In May 2023, the BBC launched BBC Verify - a team of 30 journalists whose only job is to check claims. Not just headlines. Not just quotes. Entire videos, social media posts, and viral rumors. They’ve debunked fake election results, exposed doctored videos of protests, and traced misleading audio clips back to their original sources. This wasn’t just a response to misinformation. It was a defense of trust. In 2022, 68% of UK users said they trusted the BBC. That number dropped to 59% among 18- to 24-year-olds. The BBC knew younger audiences were skeptical. So they built a team that doesn’t just report the news - they prove it’s real. BBC Verify doesn’t just publish corrections. They make short videos, interactive timelines, and explainer graphics. They tag their work clearly: “Verified by BBC.” If you see that label, it means a journalist spent hours checking sources, cross-referencing data, and contacting experts. It’s one of the most underappreciated tools in digital journalism today.The Big Change Coming: A Paywall for U.S. Visitors

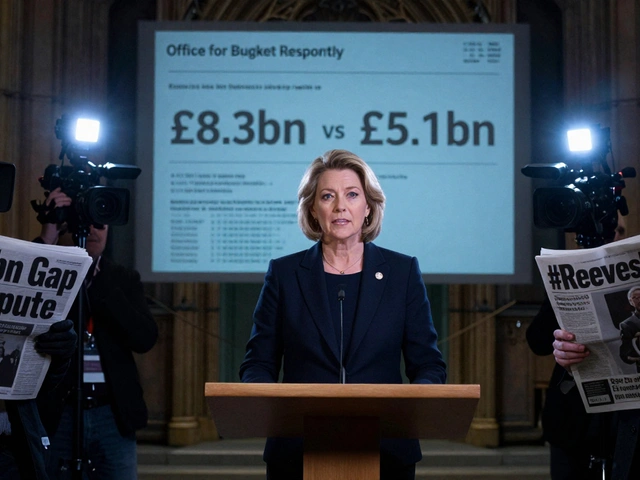

On June 26, 2025, something big will happen. If you’re in the United States and you go to BBC News Online, you’ll be asked to pay. That’s right. The BBC is putting a paywall on its international site for U.S. users. Why? Because the U.S. is the biggest market outside the UK - 18.7 million monthly visitors, according to their own data. And right now, they’re getting all of it for free. The BBC doesn’t make money from ads in the U.S. because their international site runs on a different ad model than U.S. competitors like CNN or Fox News. So instead of competing on ads, they’re going to charge for access. It’s not a full subscription like The New York Times. It’s likely a low-cost monthly fee - maybe $3 to $5 - to cover costs and fund more international reporting. This move is risky. Millions of Americans rely on the BBC for balanced coverage. But it’s also smart. The BBC is turning its global reach into revenue - without touching the UK version. The license fee stays untouched. The public service stays pure. Only the commercial side adapts.